“Is leather sustainable?”

It’s a question that echoes through design studios, boardrooms, and conscious consumer circles. And let’s be honest, the answer you often get is… fuzzy.

But here’s the deal: the answer isn’t a simple yes or no. It’s a complex tapestry woven from tradition, innovation, ethics, and hard science.

So, what does sustainable leather actually mean?

We need to move beyond vague notions. Sustainable leather isn’t just about one thing; it’s a holistic approach. It means leather produced in a way that minimizes environmental impact, upholds ethical standards for animal welfare and labor, and results in a durable, long-lasting material. It’s about finding a crucial balance between the environment, animals, and the economy.

The challenge, and also the opportunity, lies in the fact that the very definition of “sustainable leather” can shift depending on individual or company values. Some might prioritize low environmental impact above all, while others may focus more on animal welfare or the use of non-toxic chemicals. This lack of a single, universally fixed definition means that as a designer, brand, or consumer, you need to be diligent. It also means that companies genuinely committed to comprehensive sustainability can lead by setting transparent, high standards across all these facets, building trust and clear differentiation. This post aims to provide a comprehensive framework for your own assessment.

Why does this matter to you?

Whether you’re a designer, product developer, brand, or a knowledgeable consumer, your material choices have profound implications. For designers and brands, understanding leather’s sustainability impacts product quality, consumer trust, brand reputation, and your alignment with the rapidly growing demand for eco-conscious products. For knowledgeable consumers, it empowers you to make purchases that reflect your values and to invest in products built to last, not to languish in a landfill.

In this definitive guide, we’ll dissect the leather lifecycle, confront the environmental challenges head-on, explore the fascinating world of tanning technologies, unpack the often-confusing “vegan leather” debate, and highlight the path towards a genuinely more sustainable leather industry.

Ready to dive in? Let’s go.

Section 1: The Leather Story – Beyond the Surface

Before we get into the nitty-gritty of processing, it’s vital to understand where leather comes from and one of its most powerful, yet often understated, sustainability features.

The “By-Product” Perspective: A Critical Starting Point

You’ve probably heard it: leather is a by-product of the meat and dairy industries. This is a cornerstone argument in discussions about its sustainability. Organizations like the United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO) emphasize that since raw hides are generated whether we make leather or not (due to food production), the demand for leather doesn’t directly drive the number of animals raised. From this viewpoint, the leather industry is upcycling a material that might otherwise go to landfill – to the tune of about 7.3 million tons of hides annually.

However, it’s not always that simple. Other perspectives suggest that the sale of hides can provide significant additional profit to the meat and dairy industries, potentially making livestock farming more economically viable and thus, indirectly, supporting or even encouraging its scale. One source argues that “leather provides extra profit for the meat and dairy industries driving further production which ultimately leads to more cattle farming”.

Why this debate is crucial: This distinction is fundamental to how we assess leather’s environmental footprint. If leather is purely a by-product, its environmental impact is largely “inherited” from the livestock industry, encompassing factors like land use and methane emissions. Conversely, if leather’s economic value significantly contributes to the profitability and scale of that industry, then the demand for leather itself shares more direct responsibility for those upstream impacts.

The reality is likely a nuanced combination: hides are generated as a consequence of meat and dairy production, but their sale does contribute to the overall economic equation of those industries. Acknowledging this economic interplay encourages a more holistic view of responsibility and means that efforts to make leather more sustainable cannot be entirely decoupled from efforts to make the livestock industry itself more sustainable.

Expert Tip: While the “by-product” argument has validity regarding material origin, always consider the economic interplay. Acknowledging leather’s economic contribution to the livestock sector encourages a more complete view of its sustainability profile.

The Power of Durability: Leather’s Intrinsic Sustainability

Now, let’s talk about one of genuine leather’s superpowers: its exceptional durability and longevity. This isn’t just a nice feature; it’s a core sustainability credential.

High-quality genuine leather products, when properly cared for, can last for years, even decades. One source notes that real leather can last 50 to 100 years, while many synthetic alternatives often fail in under 5 years.

This longevity directly translates to reduced consumption. If a leather bag lasts 20 years, that’s potentially several less-durable synthetic bags that weren’t bought, manufactured, and ultimately discarded. This means less frequent replacement and therefore less waste – a fundamental principle of sustainable practice.

When we talk about sustainability, it’s crucial to consider the entire lifecycle and use phase of a product, not just the initial raw material sourcing or production impacts. Durability isn’t just a passive trait of leather; it’s an active lever for sustainability. For brands and designers, designing for longevity and repairability with genuine leather becomes a proactive sustainability strategy. This shifts the focus from solely “is the initial production sustainable?” to “how sustainable is the entire use-life and end-of-life of the product?”

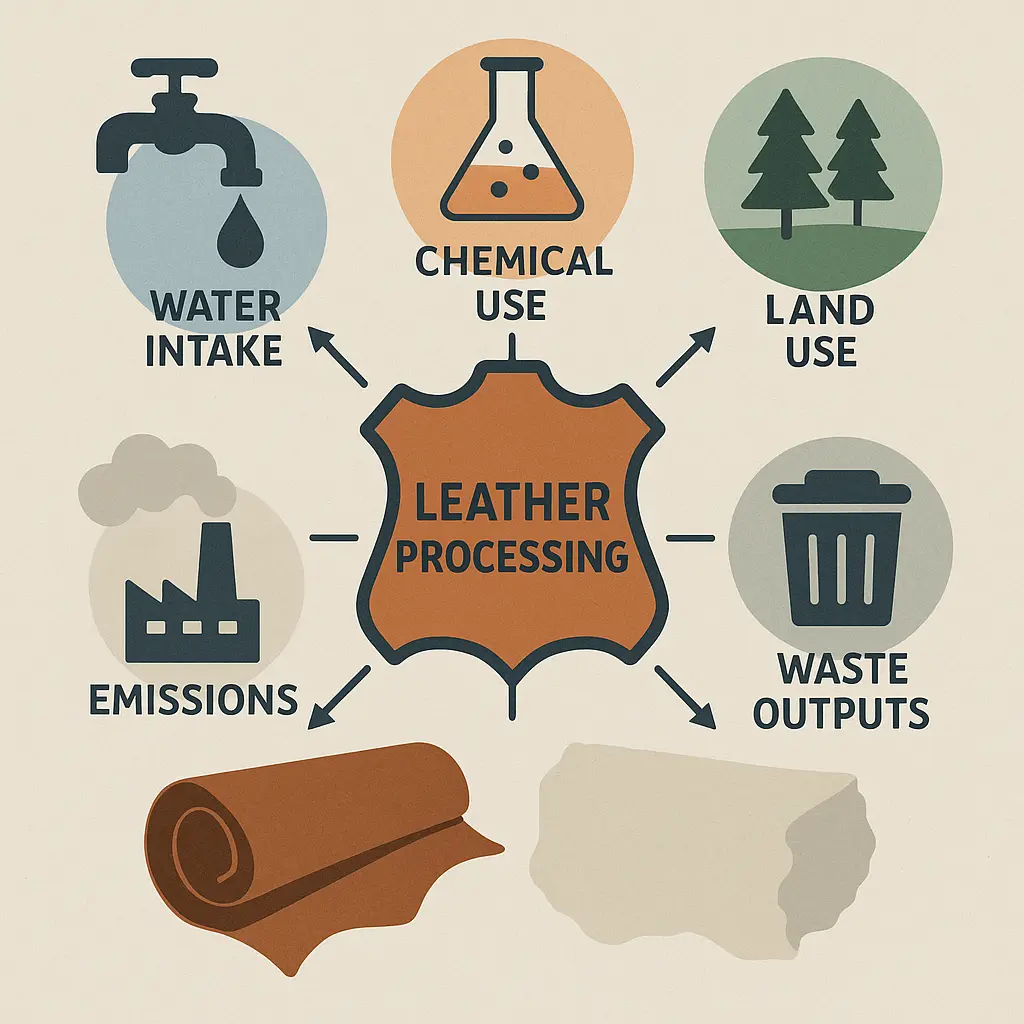

Section 2: Facing the Facts: Environmental Challenges in Conventional Leather Production

To truly appreciate the advancements in sustainable leather, we must first honestly acknowledge the historical and ongoing environmental challenges associated with conventional leather production. Transparency is key.

Water Footprint: A Thirsty Process

Traditional leather manufacturing, especially the tanning stage, is notoriously water-intensive. We’re talking large volumes. One source even quantifies this, suggesting it can take over 17,000 liters of water to create a single leather tote bag.

This high consumption doesn’t just strain local water resources, particularly in water-scarce regions; it also results in large volumes of wastewater (effluent). If this effluent isn’t managed and treated properly, it can become a significant source of water pollution.

Chemical Usage & Wastewater: The Tanning Dilemma

The transformation of raw hide into stable leather involves a cocktail of chemicals, including tanning agents (like chromium salts, which we’ll discuss more), dyes, fatliquors, and finishing agents.

Chromium is a particular point of focus. While trivalent chromium (Cr III) is the form used in tanning, there are concerns about its potential conversion to the more toxic hexavalent chromium (Cr VI) if processes are mismanaged. Other substances, like formaldehyde, have also been traditionally used and carry their own health and environmental risks.

The wastewater from these processes can be laden with these chemicals, along with high Chemical Oxygen Demand (COD), Biological Oxygen Demand (BOD), suspended solids, and sulfides. If discharged untreated, this effluent poses serious risks to aquatic ecosystems and human health.

Land Use & Deforestation: The Livestock Connection

Because leather’s primary raw material (hides) comes from livestock, the leather industry is inherently linked to animal agriculture. In some parts of the world, cattle ranching is a major driver of deforestation, particularly in sensitive ecosystems like the Amazon rainforest. One report attributes 80% of Amazon deforestation to cattle farming for meat and leather.

The production of soy for animal feed also contributes significantly to this deforestation pressure. This loss of forests has dire consequences for biodiversity, soil health, and climate change (as forests are crucial carbon sinks).

Carbon Footprint: From Farm to Finished Hide

The entire leather value chain contributes to greenhouse gas emissions. This starts on the farm with methane emissions from livestock, continues through the energy-intensive processing stages in tanneries (heating water, running machinery), and includes emissions from transporting raw materials and finished goods globally.

Waste Management: Beyond the Hide

Leather manufacturing doesn’t just use hides; it also generates significant solid waste. This includes animal trimmings, fleshings (fat and muscle removed from the hide), shavings (from evening out leather thickness), and sludge from wastewater treatment plants. Astonishingly, from 1000 kg of raw hide, nearly 850 kg can end up as solid waste.

Proper disposal of this waste is essential to prevent pollution. Increasingly, the industry is focusing on waste valorization – turning these “wastes” into valuable resources, a topic we’ll explore later.

It’s important to understand that these environmental impacts are often interconnected. For example, high water consumption leads to larger volumes of wastewater, which, if contaminated with chemicals, requires more energy and resources for treatment, potentially generating more sludge. Addressing one issue in isolation can sometimes shift the burden elsewhere. Therefore, a holistic, systems-thinking approach is crucial for developing truly sustainable solutions.

Furthermore, the stringency of environmental regulations and the level of their enforcement vary dramatically across the globe. Tanneries operating in regions with lax oversight may face lower operating costs but can have a significantly higher environmental and social footprint. This “geographic lottery” means that the origin of the leather and the specific tannery’s practices are critically important, not just the general type of leather. A “vegetable-tanned leather” from an unregulated facility might, in reality, have a worse overall impact than a “chrome-tanned leather” from a state-of-the-art, LWG Gold-rated facility in a highly regulated region. This underscores the vital importance of traceability and certifications that verify actual performance.

Key Consideration: Acknowledging these challenges isn’t about condemning leather; it’s about setting the stage for understanding the solutions. The good news is that the industry is actively innovating and implementing ways to mitigate these impacts, which we’ll explore next.

Section 3: The Art & Science of Tanning: A Deep Dive into Processes & Impacts

Tanning is the magical, transformative process at the heart of leather making. It’s what converts a raw, perishable animal hide into the durable, versatile, and beautiful material we know as leather. This is achieved by stabilizing the collagen protein fibers within the hide, preventing decomposition and imparting desired physical properties like strength, flexibility, and resistance to heat and moisture.

Let’s explore the main tanning methods, their characteristics, and their environmental considerations.

Chrome Tanning: The Industry Workhorse

If you’re interacting with leather, there’s a high chance it was chrome-tanned. This method is the dominant force in the industry, accounting for an estimated 75-90% of all leather produced globally.

The process primarily uses trivalent chromium (Cr III) salts, most commonly chromium sulfate. Before the main tanning, hides are typically “pickled” – treated with acid and salt to prepare them for chromium penetration. The resulting tanned hides often have a characteristic pale blue color, earning them the name “wet blue”.

Chrome tanning is popular due to several benefits. It offers speed and cost-effectiveness, being a relatively quick process often completed within a day, making it efficient for large-scale production. It also produces consistent results with uniform quality. Furthermore, it yields leather with desirable properties such as softness, suppleness, good tensile strength, excellent thermal stability (high shrinkage temperature, often >95°C ), and good water resistance. It also generally takes dyes well, allowing for a wide range of vibrant colors.

However, there are drawbacks and environmental concerns. A key concern is chromium in the effluent, as not all chromium salts are absorbed, and a significant portion can remain in wastewater if not managed properly, with concentrations potentially reaching 1500-3000 mg/L. There’s also the risk of hexavalent chromium (Cr VI) formation; while Cr III is used, it can oxidize into the toxic Cr VI under certain mismanagement conditions. Reputable tanneries and standards like the LWG protocol have strict measures against this. Additionally, sludge disposal from wastewater treatment can generate chrome-containing sludge requiring careful hazardous waste disposal. The biodegradability of chrome-tanned leather is also contested by some, who argue it’s less biodegradable than vegetable-tanned leather, though all leather eventually biodegrades.

It’s crucial to understand that modern, responsible tanneries have made huge strides in managing chromium. This includes implementing high-exhaustion tanning systems to improve chromium uptake, utilizing chrome recovery and recycling to reuse chromium from effluent, and employing advanced wastewater treatment plants. The LWG audit protocol heavily emphasizes and rewards these best practices in chrome management.

Vegetable Tanning: The Ancient, Natural Art

Vegetable tanning is the oldest known method of tanning leather, a craft passed down through millennia. It relies on the power of natural tannins – complex polyphenolic compounds extracted from various parts of plants.

This method uses tannins derived from sources like tree bark (oak, chestnut, quebracho), leaves (sumac), fruits (myrobalan), and pods (tara). Hides are traditionally soaked in a series of vats containing increasingly strong concentrations of these tannin liquors, often in large wooden drums. The process is slow and patient.

Vegetable-tanned leather boasts several characteristics and benefits. It produces leather with a unique aesthetic, offering a distinctive natural beauty, rich warm tones, and a characteristic earthy or sweet smell. It is also famous for aging gracefully, developing a beautiful patina over time and with use. Often considered more environmentally friendly due to its reliance on natural, renewable inputs, it can be highly biodegradable if not heavily treated with synthetic finishes, with some sources suggesting unfinished vegetable-tanned leather is 100% biodegradable. Furthermore, it can produce very strong and durable leather.

Despite its advantages, there are drawbacks and considerations. A key difference is the much longer process time, which can take weeks or even months (e.g., up to 60 days for heavy sole leather ), making it more labor-intensive and generally more expensive. While inputs are natural, the process may use several times the amount of tannins compared to chromium in chrome tanning, and water usage can also be substantial. Even though tannins are natural, high concentrations of organic matter in the wastewater can lead to a high BOD/COD load, requiring robust effluent treatment. In terms of leather properties, it typically results in a firmer, less stretchy leather than chrome-tanned, though this varies. It can be more susceptible to water staining, discoloration from iron, and heat damage, with a generally lower shrinkage temperature (around 70-75°C ). Finally, the natural color of the tannins restricts the limited color palette achievable, especially for light or bright shades.

Emerging & Alternative Tanning Technologies: The Quest for Greener Chemistry

The drive for sustainability is fueling innovation in tanning chemistry, leading to a range of “chrome-free” alternatives. It’s important to remember that “chrome-free” doesn’t automatically mean “problem-free.” Each alternative has its own profile.

Aldehyde Tanning (e.g., Glutaraldehyde, “Wet-White”) is often marketed as “chrome-free”. Glutaraldehyde is a common agent, while formaldehyde’s use is declining due to health concerns (it’s a known irritant and potential carcinogen ). This process produces leather that is pale cream or white before dyeing, hence “wet-white”, ideal for light shades. The resulting leather can be soft, pliable, and water-resistant, with a shrinkage temperature around 75-80°C. However, glutaraldehyde itself can be an irritant and toxic to aquatic life if mismanaged, and aldehyde-tanned leathers may require more post-tanning chemicals, adding to the effluent load.

Synthetic Tanning Agents (Syntans) are man-made organic chemicals, often derived from phenolic, naphthalene, or melamine compounds. They are widely used, frequently in combination with other agents (especially in retanning) to modify properties. Syntans offer excellent control over final leather characteristics like softness, fullness, grain tightness, uniformity, color brightness, and dye uptake, and can improve resistance to shrinkage and light. There’s a growing range of modern “eco-syntans” designed to be more environmentally friendly, with reduced toxicity, improved biodegradability, and freedom from harmful substances, potentially reducing water usage. The environmental profile of syntans varies hugely, so it’s crucial to know the specific chemistry.

Zeolite Tanning (e.g., Zeology™) is a relatively new chrome-free, aldehyde-free, and heavy-metal-free system using zeolite minerals. Proponents highlight its improved sustainability profile. Zeolite-tanned leathers reportedly have good water absorption properties without excessive swelling. It produces a “wet-white” type leather with a shrinkage temperature around 70-75°C, and the leather can be soft and elastic. As a newer technology, its long-term performance and scalability are still being established, and the leather will contain aluminum from the zeolite structure, distinct from traditional aluminum salt tanning.

The evolution of tanning is a continuous story of balancing performance, cost, and environmental/social impact. Chrome tanning became dominant for its efficiency and the versatile leather it produces. Vegetable tanning maintained its place for unique aesthetic and traditional qualities. Now, environmental awareness is a major driver, pushing innovation towards alternatives that reduce negative impacts without significantly compromising performance or drastically increasing cost. The “best” tanning method is often context-dependent, factoring in the intended application, desired leather properties, available technology, and the regulatory environment.

To help you navigate this complex landscape, here’s a comparative overview:

Table 1: Comparative Overview of Key Tanning Methods

| Tanning Method | Key Chemical Inputs | Primary Environmental Concerns | Effluent Profile Highlights | Resulting Leather Characteristics (Durability, Feel, Water Resistance, Typical T<sub>s</sub> °C, Raw Color, Dyeability, General Biodegradability Indication) | Common Applications |

| Chrome Tanning | Chromium (III) sulfate, acids, salts | Chrome in effluent, potential Cr(VI) risk (if mismanaged), chrome sludge | Chromium, high salts, moderate COD/BOD | High durability, soft to firm, good water resistance, T<sub>s</sub> >95°C, “Wet blue” color, excellent dyeability for wide color range. Biodegradability moderate, depends on finishing. | Footwear, apparel, upholstery, automotive, majority of leather goods |

| Vegetable Tanning | Plant tannins (from bark, wood, leaves, fruits, pods) | High tannin/organic load in effluent (BOD/COD), potentially high water usage, longer process time | High BOD/COD, natural organics | Very durable (can improve with age), typically firmer (can be softened), develops patina, fair water resistance (can stain), T<sub>s</sub> ~70-75°C, Natural tan/brown shades, limited bright colors. Good biodegradability if lightly finished. | Saddlery, belts, wallets, craft items, shoe soles, traditional goods |

| Aldehyde Tanning (Glutaraldehyde) | Glutaraldehyde, other aldehydes (historically formaldehyde) | Toxicity of some aldehydes (e.g., formaldehyde), glutaraldehyde in effluent, may need more post-tanning chemicals | Potential aldehyde residuals, higher COD from auxiliary chemicals | Good durability, often very soft, good water resistance, T<sub>s</sub> ~75-80°C, “Wet white” (pale cream), excellent for pastel/light dyeing. Biodegradability varies with specific aldehyde and finish. | Automotive leather, washable leathers (chamois), children’s shoes, some apparel |

| Zeolite Tanning (e.g., Zeology™) | Zeolite minerals (aluminosilicates) | Newer tech, full lifecycle impacts still being broadly assessed; aluminum content in leather (from zeolite) | Mineral content, generally lower organic load than veg-tan | Good durability, soft and elastic, good water absorption (comfort), T<sub>s</sub> ~70-75°C, “Wet white”, good dyeability. Promoted as more sustainable, biodegradability depends on finishes. | Footwear, apparel, potentially automotive |

| Synthetic Tannins (Syntans) | Phenolic, naphthalene, melamine derivatives, others | Varies widely by specific syntan chemistry; older types may have eco-concerns, newer ones designed to be eco-friendlier | Variable based on syntan type and usage | Used to modify properties: can enhance softness, fullness, grain tightness, dye uptake, lightfastness. Often used in retanning. T<sub>s</sub> varies. Color impact depends on use. Biodegradability depends heavily on specific syntan. | Widely used in retanning for most leather types to fine-tune properties |

Export to Sheets

Data sources for table:. T<sub>s</sub> = Shrinkage Temperature.

Expert Tip: When discussing tanning with suppliers, don’t just ask what tanning method they use, but how they manage its impacts. For chrome tanners, inquire about their chrome exhaustion rates, how they treat chrome-containing effluent, and if they have chrome recovery systems. For vegetable tanners, ask how they manage the BOD/COD load from tannins and about their water conservation practices. For all tanners, request data on water and energy consumption per hide and ask about certifications like LWG.

Understanding the nuances of these processes and asking the right questions is key to sourcing leather more responsibly.

Section 4: The Path to Greener Leather: Innovations Transforming the Industry

The leather industry isn’t standing still. Faced with environmental challenges and growing demand for sustainable materials, it’s buzzing with innovation. Let’s look at some of the key advancements paving the way for a greener future.

Smarter Water & Energy Use: Doing More with Less

Water and energy are two major resource consumers in leather production. Smart tanneries are tackling this head-on by implementing closed-loop systems and water recycling to reuse water within various stages, dramatically reducing freshwater consumption and effluent volume. The gold standard is Zero Liquid Discharge (ZLD), where systems aim to treat and recycle all wastewater on-site, offering huge benefits for water conservation and resource recovery, though initial investment can be challenging. Additionally, tanneries are adopting more energy-efficient machinery, optimizing processes, and investing in renewable energy sources like solar panels or biomass boilers, with audits like LWG assessing and encouraging such practices.

Waste Valorization: From “Trash” to Treasure

As we saw earlier, leather processing can generate a lot of solid waste. The exciting shift here is towards waste valorization – transforming these “waste” streams into valuable new products, instead of just sending them to landfill. This is circular economy in action. Examples include creating recycled/reconstituted leather from scraps and trimmings; extracting collagen from untanned waste for food, cosmetic, or medical uses; processing organic waste into fertilizers and soil conditioners; generating biofuel from fats and organic matter; fabricating composite materials from buffing dust for footwear components; and exploring microbial valorization to convert tannery waste into enzymes or biopolymers using microorganisms.

This approach is not just about reducing landfill; it’s a fundamental shift towards a circular economy model for leather. It changes the perception of by-products from a liability to an asset. This can improve the overall material efficiency of the industry, reduce reliance on virgin resources for other products, and even create new revenue streams, making sustainable practices more economically viable.

Regenerative Agriculture: Greener Pastures for Hides

A significant portion of leather’s environmental footprint is tied to conventional livestock farming – issues like land degradation, deforestation, and greenhouse gas emissions. Regenerative agriculture offers a promising alternative.

This approach to farming focuses on practices that actively improve soil health, enhance biodiversity, increase water infiltration and retention, and sequester carbon from the atmosphere back into the soil. When hides are sourced from animals raised on regenerative farms, it means the raw material for leather is coming from a system that aims to be environmentally positive, or at least significantly less damaging, than conventional agriculture. This creates a potential symbiotic relationship: demand for verifiably “regeneratively farmed” hides could provide an additional economic incentive for farmers to adopt these beneficial practices. This could, in turn, improve the sustainability profile of both the meat/dairy and leather industries. It moves the focus from merely “less bad” farming to “positively good” farming, with leather as a co-beneficiary and potential driver. Traceability is, of course, paramount to verify these claims.

Pioneering initiatives like British Pasture Leather are working to provide traceable leather from regenerative farms in the UK.

Advanced & Bio-Based Tanning Agents: The Next Generation

The quest for cleaner tanning chemistry is ongoing, with significant research focused on new tanning agents that are less toxic, more biodegradable, and derived from renewable resources. This includes continuous improvements in existing chrome-free systems as well as entirely novel organic tanning agents. A fascinating example is the development of an amphoteric organic chrome-free tanning agent derived from recycling waste leather itself. In this process, collagen protein is extracted from chrome-containing leather waste (after de-chroming it) and then chemically modified to create a new tanning agent. This agent has shown promising results, producing leather with good properties (like a shrinkage temperature around 85°C and excellent dye uptake) while also leading to tannery wastewater that is more easily degradable. This is a brilliant example of closing the loop – turning waste into a key processing chemical.

Key Consideration: These innovations showcase the leather industry’s remarkable capacity for positive change. However, widespread adoption of these greener technologies requires investment, collaboration across the entire supply chain (from chemical suppliers to brands), and often, supportive regulatory frameworks or strong consumer demand pushing for these better alternatives.

Section 5: “Vegan Leather” Unpacked: Sustainable Hero or Hidden Villain?

The term “vegan leather” has exploded in popularity, often presented as the clear sustainable choice over animal-derived leather. But is it really that straightforward? Let’s peel back the layers.

Defining the Alternatives: A Crowded and Confusing Field

“Vegan leather” isn’t one single material. It’s an umbrella term for a vast and often confusing array of materials designed to mimic the look and feel of genuine leather without using any animal products.

The main players include PU (Polyurethane) and PVC (Polyvinyl Chloride) “Leathers,” which are essentially fabrics coated with petroleum-based plastic, widely available and inexpensive. Then there are the newer Plant-Based Leathers, often marketed with a strong sustainability narrative. Common examples are Piñatex®, made from pineapple leaf fibers typically mixed with PLA and coated with a petroleum-based resin; Desserto®, derived from nopal cactus leaves with advanced formulations up to 90% plant-based using a proprietary bio-polymer; and Mylo™ (Mushroom/Mycelium Leather), grown from the root-like structure of fungi. You’ll also hear about leathers from apple peels, grape skins, cork, and teak leaves.

A Quick Note on “Eco-Leather”: Be very wary of this term! Historically, “eco-leather” often referred to purely synthetic, petroleum-based leathers like PU or PVC. To combat this confusion and protect consumers, some regions have introduced regulations. For instance, an Italian Decree Law from 2020 restricts the use of the term “leather” (pelle) exclusively to products of animal origin. Expert Tip: Always ask: What is this “eco-leather” actually made of? Get the specific material composition.

Durability & Lifespan: The Achilles’ Heel?

This is where a major difference often emerges. Genuine Leather is renowned for its exceptional longevity, with well-cared-for goods lasting many years, often decades. In contrast, Synthetic Leathers (PU, PVC) generally have a much shorter lifespan, prone to cracking, peeling, and delamination, often within just 1-5 years, with one user noting they’ve “never met a pleather that didn’t start flaking less than two years after use”. The durability of Plant-Based Leathers varies widely: Cork leather is a standout, potentially lasting 15-20 years; Desserto® (cactus leather) is claimed to last around 8-10 years; while others like mycelium, Piñatex®, and apple skin leather generally fall into the 2-6 year range.

This shorter lifespan of most synthetic and many plant-based alternatives is a critical sustainability issue. If a product needs to be replaced two, three, or even five times more frequently than a durable genuine leather counterpart, the cumulative environmental impact of producing and disposing of those multiple items can quickly outweigh any perceived benefits of the alternative material itself. This cycle of frequent replacement fuels higher consumption and generates significantly more waste.

The Plastic Predicament: What Are They Really Made Of?

Here’s a crucial point often glossed over in marketing: many so-called “vegan” and “plant-based” leathers still contain a significant percentage of plastics – typically polyurethane (PU), polyvinyl chloride (PVC), or other synthetic polymers. These plastics are used as binders to hold the plant fibers together, as coatings to give a leather-like finish and some water resistance, or as the main component itself.

One source indicates that even innovative plant-based options like those from mushrooms and pineapple are often “mixed with PU or PVC in the order of 80 to 90% of the total to form the composite material”. Piñatex®, for example, while using pineapple leaf fibers and PLA (a bio-plastic), is typically coated with a petroleum-based resin, which currently renders the final material non-biodegradable. Desserto® states its most advanced forms are up to 90% plant-based, which implies that around 10% is their proprietary (though partially bio-derived) polymer or other components.

This “plant-based” halo effect can be misleading. Consumers may believe they are buying a wholly natural or biodegradable product when, in reality, it may still be predominantly plastic, with all the associated environmental concerns of fossil fuel reliance, chemical processing, and end-of-life persistence. Full transparency in material composition is vital.

End-of-Life Realities: A Mounting Concern

What happens to these materials when they wear out or are discarded? Regarding biodegradability, genuine leather (responsibly tanned & not heavily coated) can biodegrade naturally, with decomposition times cited as 10-45 years. PU/PVC leathers are not biodegradable, persisting for hundreds of years and fragmenting into microplastics; imitation leather can take over 500 years to decompose. For plant-based leathers, it’s complex: Desserto® claims partial biodegradability under specific conditions, while Piñatex® is currently non-biodegradable due to its coating, though a bio-based solution is in development. The plastic binders and coatings are often the main barrier. Recyclability is generally very limited for most synthetic and mixed-material vegan leathers, though Desserto® claims its materials can be recycled. Finally, the physical degradation of all plastic-based leathers contributes to microplastic pollution, a pervasive global problem.

To provide a clearer picture, let’s compare these materials side-by-side:

Table 2: Genuine Leather vs. Common “Vegan” Alternatives – A Sustainability Snapshot

| Material Type | Primary Composition | Typical Lifespan (Years) | Biodegradability/Disposal Issues | Key Environmental Production Concerns | Key Strengths | Key Weaknesses |

| Genuine Leather (responsibly tanned) | Animal hide (collagen) | 20-50+ (even 100 ) | Biodegradable (conditions & finish dependent ). | Livestock impacts (land use, emissions if not regenerative), tanning effluent (if poorly managed). | Extreme durability, repairable, natural feel, develops patina, breathable. | Ethical concerns (if poorly sourced/animal welfare not ensured), higher initial cost, weight. |

| PU (Polyurethane) Leather | Polyurethane plastic coating on textile base (often polyester) | 1-5 | Non-biodegradable; breaks down into microplastics; persists for centuries in landfill. | Fossil fuel-based (petroleum), chemical solvents in production, energy-intensive. | Low cost, versatile appearance, lightweight. | Poor durability (cracks, peels ), plastic feel, not breathable, microplastic pollution, fossil fuel reliance. |

| PVC (Polyvinyl Chloride) Leather | Polyvinyl chloride plastic coating on textile base | 1-3 | Non-biodegradable; can leach toxic chemicals (e.g., phthalates, dioxins if incinerated); microplastics. | Fossil fuel-based, chlorine production, use of plasticizers (often phthalates), potential release of harmful VOCs & dioxins. | Very low cost, highly water-resistant. | Very poor durability, environmental & health concerns of PVC, often stiff, not breathable, microplastic pollution. |

| Piñatex® (Pineapple Leaf Leather) | Pineapple leaf fibers, PLA (polylactic acid – a bio-plastic), petroleum-based PU resin coating | 2-4 | Currently non-biodegradable due to resin coating; some components (fibers, PLA) are biodegradable. Company working on bio-based coating. Microplastic potential from coating. | Petroleum-based resin coating. Agricultural impacts of pineapple farming (if not solely from waste stream). PLA production has its own footprint. | Uses agricultural waste stream (pineapple leaves), unique texture, lower water use than some crops. | Durability can be limited, reliant on plastic coating for performance & water resistance, cost, current non-biodegradability. |

| Desserto® (Cactus Leather) | Nopal cactus (up to 90% plant-based in some versions), proprietary bio-polymer | 8-10 | Partially biodegradable under specific anaerobic thermophilic conditions. Recyclable (chemically/mechanically ). | Production of bio-polymer. Agricultural inputs for cactus (though cactus is generally low-input). | High plant content, reduced water use (cactus is drought-resistant), soft feel, claims of good durability. | Newer material, long-term real-world durability across all applications still being proven, cost, partial biodegradability. |

| Mylo™/Mushroom Leather (Mycelium-based) | Fungal mycelium, may have textile backer and synthetic finishes | 4-6 | Potentially biodegradable if finishes/backers are also bio-based. Otherwise, similar issues to other composites. | Energy for controlled cultivation of mycelium, scalability, chemicals for finishing. | Novel material, potential for good biodegradability, unique aesthetic, grown not farmed (less land use). | Current scalability, cost, durability compared to traditional leather still under development for many applications, performance dependent on finishes/backers. |

Data sources for table:. Lifespans are typical estimates and can vary with quality and care.

Expert Tip: When evaluating any “vegan leather,” especially plant-based ones, dig deep. Ask for a full material composition disclosure to understand the percentage of actual plant matter versus synthetic components. Inquire about real-world durability data, not just lab tests. And seek clear end-of-life information, clarifying if it’s truly biodegradable in accessible conditions or requires specific industrial facilities.

The allure of “vegan” is strong, but true sustainability requires looking beyond the label to the full lifecycle and material reality.

Section 6: The Ethical Imperative: Animal Welfare & Social Responsibility

True sustainability isn’t just about environmental metrics. It stands on a three-legged stool: environmental stewardship, social responsibility (for people), and ethical treatment (for animals). All three are non-negotiable.

Animal Welfare Standards: Beyond the Hide

As we’ve established, the hides and skins used for leather are overwhelmingly by-products of the meat and dairy industries. This means that the welfare of the animals on farms, during transport, and at the point of slaughter is an integral part of sourcing leather ethically.

A widely recognized international framework for animal welfare is the “Five Freedoms”, which include freedom from hunger and thirst; freedom from discomfort; freedom from pain, injury, or disease; freedom to express normal behaviors; and freedom from fear and distress.

To ensure and verify good animal welfare, responsible sourcing and traceability are key. This means being able to trace hides back through the supply chain, ideally from the tannery to the slaughterhouse, and even to the farm of origin. Leading brands and initiatives are pushing for this; for example, Deckers Brands aims to source 100% of its leather from LWG-certified tanneries and has commitments for traceability from deforestation-risk areas. The Sustainable Leather Foundation (SLF) is also working to establish a harmonized global standard for animal welfare in the leather supply chain. Most ethical sourcing policies explicitly prohibit hides from animals slaughtered solely for pelts or skinned alive, and often list prohibited exotic species.

Improving animal welfare for leather requires influencing and collaborating with the upstream meat and dairy industries. It’s not enough for a tannery to have excellent environmental practices if its raw material comes from systems with poor animal welfare. This makes partnerships and robust agricultural policies vital.

Fair Labor Practices: The Human Element

The journey of leather doesn’t just involve animals and the environment; it involves many human hands. Ensuring safe working conditions, fair wages, reasonable working hours, and the ethical treatment of workers in tanneries and manufacturing facilities is a critical pillar of sustainability.

Tanneries, particularly in some developing countries with weaker regulatory oversight, can present significant labor challenges. These include exposure to hazardous chemicals like chromium and formaldehyde without adequate protection, leading to serious health problems. Workers may also face low wages and long hours, often not complying with labor laws. Tragically, there are reports of child labor and forced labor in some parts of the supply chain. Furthermore, a lack of safety measures, such as inadequate equipment or poorly maintained machinery, can lead to accidents. The importance of transparency and audits cannot be overstated, as a lack of transparency in complex global supply chains makes it difficult to monitor these abuses. Social audits and certifications, like the LWG audit protocol which includes a section on social responsibility, play a role here.

A leather product cannot be considered truly “sustainable” if it is produced at the expense of human health, safety, and dignity. The social pillar of sustainability is non-negotiable. Brands and manufacturers have a profound responsibility to ensure their supply chains are free from exploitation. This requires robust auditing, unwavering transparency, and a willingness to invest in suppliers who demonstrably uphold ethical labor standards, even if it means higher costs. The pursuit of “cheap” leather can inadvertently perpetuate these poor conditions.

Key Consideration: True sustainability demands a holistic view. Brands committed to this path must extend their due diligence far beyond just environmental impacts to encompass robust animal welfare policies and verifiable fair labor practices throughout their supply chains.

Section 7: Your Guide to Credibility: Navigating Leather Certifications & Standards

In a complex global industry like leather, how can you, as a designer, brand, or consumer, verify claims about sustainability? This is where third-party certifications and standards come into play. They provide a framework for assessing practices, verifying claims, and offering a degree of assurance.

Why Certifications Matter

Certifications are important because they establish benchmarks defining “good” performance in areas like environmental management and social responsibility. They provide independent verification through third-party auditors, offering more credibility than self-declarations. Many schemes drive continuous improvement through tiered levels or regular re-audits. Finally, they increase transparency, making it easier for brands to select responsible suppliers and for consumers to make informed choices.

It’s important to see certifications as markers of a supplier’s commitment to and progress on the sustainability journey, rather than a guarantee of absolute, static “perfection.” A tannery achieving a certain level is making significant efforts, and protocols themselves evolve, meaning standards today are likely higher than in the past.

Leather Working Group (LWG): The Industry Benchmark

The Leather Working Group (LWG) is arguably the most well-known and widely adopted certification specific to the leather manufacturing industry. It’s a multi-stakeholder initiative involving brands, retailers, leather manufacturers, chemical suppliers, and technical experts, all committed to driving best practices and positive environmental and social change.

The LWG Audit Protocol is central to the program, offering a comprehensive assessment of a tannery’s operational performance across 17 key sections. These sections cover water and energy usage, Environmental Management Systems (EMS), chemical management (including a Chemical Management Module – CMM), waste management, effluent treatment, occupational health and safety, and crucially, traceability. The LWG audit assesses a tannery’s ability to trace raw material back to the slaughterhouse, rated separately, and also has a Trader Audit Standard for intermediaries. Social Responsibility is also addressed, with the LWG Leather Manufacturer Audit protocol including a dedicated section that recognizes credible third-party social audits.

Based on their audit score, tanneries are awarded certification levels: Gold (85% or higher), Silver (75% or higher), Bronze (65% or higher), or Audited (50% or higher, indicating a pass but below medal rating). A tannery automatically fails if it lacks valid legal operating permits or fails critical minimums. The LWG audit, initially for bovine leather, now also assesses tanneries producing leather from caprine, porcine, ovine, and some exotic origins.

Other Notable Certifications & Standards

While LWG is central to tannery operations, other certifications address different aspects of sustainability relevant to leather products. Cradle to Cradle Certified® (C2C) is a rigorous, holistic product standard assessing materials across five categories: Material Health, Product Circularity, Clean Air & Climate Protection, Water & Soil Stewardship, and Social Fairness. The Global Organic Textile Standard (GOTS) can apply if leather is from organically farmed animals and processed with non-toxic chemicals and responsible resource use. ISO 14001 is an international standard for Environmental Management Systems (EMS) that many responsible tanneries implement. The Sustainable Leather Foundation (SLF) is developing a standard for a harmonized approach to animal welfare. Leather Naturally is a non-profit promoting sustainable leather, potentially offering its own certification or resources.

No single certification covers all bases perfectly. For instance, LWG is very strong on the operational impacts within the tannery itself but relies on other systems or information for detailed farm-level animal welfare or the full lifecycle of a finished product. This is why a combination of certifications and deep supply chain transparency often provides the most robust assurance.

Expert Tip: Certifications are valuable tools, but they are not a silver bullet. Understand the scope of each certification—what it covers and what it doesn’t. Look for tiers in certifications like LWG or C2C, as the level achieved indicates performance. Consider a portfolio of certifications for a more holistic view of sustainability. And always ask for proof of certification, such as certificates or audit summaries.

Section 8: Driving Change: Your Role in a More Sustainable Leather Ecosystem

The journey towards a more sustainable leather industry isn’t just up to tanneries or chemical companies. Everyone in the value chain has a crucial role to play – from the designers sketching initial concepts to the brands bringing products to market, and ultimately, to the consumers making purchasing decisions.

The collective power of informed choices can create a significant “demand-side pull,” accelerating the adoption of sustainable practices. When designers, brands, and consumers actively seek out and prioritize more responsible options (like LWG-certified leathers, traceable materials, or products from regenerative agriculture), they send a strong market signal. This, in turn, incentivizes more suppliers to invest in the necessary practices, technologies, and certifications to meet that growing demand and gain a competitive edge. Education and awareness are therefore critical levers for transforming the entire industry.

For Designers & Product Developers: Crafting a Better Future

As a designer or product developer, you can integrate sustainability from the outset. Practice informed material selection by digging deeper than surface aesthetics; understand origins, tanning processes, and certifications, and don’t hesitate to ask suppliers detailed questions. Design for durability and repairability, leveraging leather’s longevity to create products built to last and easily repaired. Aim to minimize waste in design and production by optimizing cutting patterns and finding uses for offcuts. Finally, explore innovative and lower-impact leathers, staying informed about new technologies, critically assessed bio-based alternatives, and leathers from sustainable agricultural systems.

For Brands: Leading with Integrity & Transparency

Your brand’s choices can significantly shape the market. Embrace radical supply chain transparency by mapping your leather supply chain, knowing your tanneries, understanding hide origins, and sharing this information with customers. Invest in responsible sourcing by prioritizing suppliers with strong environmental and social credentials, such as LWG medal-rated tanneries and those with robust animal welfare policies. Commit to continuous improvement by setting clear, measurable sustainability goals for your leather sourcing and products, tracking progress, and being transparent about successes and challenges. Educate your consumers authentically, clearly communicating your sustainability efforts and the benefits of responsibly made leather, while avoiding greenwashing. Lastly, support industry initiatives and collaboration by working with organizations like LWG and the Sustainable Leather Foundation to advance sustainability in the sector.

For Knowledgeable Consumers: Voting with Your Wallet & Your Voice

Your purchasing decisions send powerful signals. Ask questions and demand transparency from brands about leather origins and production methods before buying. Support ethical and sustainable brands that demonstrably prioritize responsible practices and look for credible certifications. Invest in quality and longevity, opting for well-made, durable leather goods over fast fashion items to reduce consumption and waste. Care for your leather through proper cleaning and conditioning to extend its life. Repair, don’t replace, when possible, utilizing specialists to give items a new lease on life. And fundamentally, reduce overall consumption by considering if a new purchase is truly necessary or if alternatives like repairing, repurposing, borrowing, or buying second-hand are viable.

The Collective Impact: Small Choices, Big Changes

It might seem like individual choices don’t matter much in the face of such a large global industry. But they do. Every time a designer specifies a more sustainable leather, every time a brand invests in a certified tannery, every time a consumer chooses a product based on its ethical credentials, it contributes to a larger shift.

Collectively, these conscious choices create the momentum needed to drive the leather industry towards a future where quality, beauty, and sustainability go hand in hand.

Conclusion: So, Is Leather Sustainable? The Verdict & The Journey Ahead

We started with a big question: “Is leather sustainable?” After journeying through its lifecycle, tanning processes, alternatives, and ethical dimensions, it’s clear that leather’s sustainability isn’t a binary “yes” or “no.” It exists on a spectrum, profoundly influenced by countless decisions made from the farm to the finished product.

Let’s recap the core realities. Conventional leather production, without robust controls, faces significant environmental and ethical challenges like high water and chemical use, links to deforestation, and potential poor labor conditions. However, the leather industry is not static; it is rich with innovation and a growing commitment from many players to address these issues.

The Verdict: Genuinely Sustainable Leather IS Achievable.

But it’s not a given. It requires a holistic and unwavering commitment across the board. This includes responsible raw material sourcing with traceable hides from systems prioritizing animal welfare and minimizing environmental degradation. It demands best-in-class tanning and finishing using the cleanest technologies, minimizing resource consumption, and managing chemicals effectively. Waste valorization and circularity are crucial, viewing by-products as resources. Upholding ethical labor practices ensuring safe and fair conditions is non-negotiable. Finally, it involves designing for product longevity and thoughtful end-of-life, creating durable goods that can be repaired and whose materials can biodegrade or be repurposed.

Understanding these nuances – the complexities, the challenges, and the solutions – is paramount for anyone involved in creating, sourcing, or purchasing leather goods. It allows you to move beyond simplistic labels and marketing hype, and to make choices that genuinely support a more sustainable and ethical future for this remarkable, enduring material.

The Journey Ahead:

The path to a universally sustainable leather industry is an ongoing journey. It requires continuous innovation in chemistry, technology, agriculture, and waste utilization. It needs significant investment from tanneries, brands, and research institutions. Deep collaboration across the entire value chain is essential, as is unwavering transparency for tracking progress and maintaining accountability. And fundamentally, it depends on conscious choices from every stakeholder.

At Saccent, we are dedicated to being at the forefront of sustainable leather manufacturing. We believe that true quality encompasses not just the aesthetic and performance of our leathers, but also the integrity of their production. We invite you to explore our commitment to practices like sourcing from LWG Gold-certified tanneries, our investment in water recycling technologies, and our rigorous chemical management protocols.

Partner with us to create exceptional leather goods that don’t just look good and feel good, but do good. Contact us today to discuss how our expertise in sustainable leather can elevate your next collection and help you meet the growing demand for responsibly made products.

Alternatively, learn more about our specific sustainable leather offerings and our detailed sustainability initiatives.

About Saccent

For 30 years, Saccent has been a trusted partner for brands seeking premium leather manufactured with a deep commitment to environmental stewardship and ethical production. We combine artisanal heritage with cutting-edge technology to deliver leathers that meet the highest standards of quality and sustainability, ensuring that the beauty of leather can be enjoyed responsibly for generations to come.